More about The British East India Company – The Silver Triangle, 2019

A group of five translucent porcelain vases with cobalt painting and silver foil on lids

Made by the artist in Jingdezhen, China

The story of the five vases relates, in the first part, to the economic trade between Britain, India and China facilitated by the British East India Company; and in the second, to the cross-cultural flow of art and ideas that can be salvaged from the wreckage of such trade by enlightened societies.

The British East India Company was a joint-stock company created in 1600 to trade with Mughal India and the East Indies, in spices, salt, indigo dye, saltpetre, cotton, silk, tea and opium. The silver triangle was a term coined to describe the value in silver bullion of goods traded between Britain, India and China. China exported much but imported little so a trade imbalance was, in the early days, settled by payment in British silver bullion to the Middle Kingdom. According to the World Economic Forum, for two hundred years up until the 1820’s China remained the largest economy in the world.

In the 18

th Century tea (Camellia Sinensis) became a popular drink in Britain, disguising the taste of tainted water, and could only be sourced in commercial quantities from China. In order to stop the flow of silver out of Britain to pay for Chinese tea; Indian opium (Papaver Somniferum) grown in Bengal under the control of the British East India Company, was sold illegally through of a series of middlemen to the Cantonese Cohongs (Chinese trading companies).

Although the smoking and importing of opium was banned in China; in the year 1838 near to 900 tons of Bengal opium was smuggled into Chinese controlled Cohongs. Its devastating effects on the Chinese population led the JiaQing Emperor to appoint Special Imperial Commissioner, Lin Zuxu, to curb smuggling.

Commissioner Lin wrote and elegant entreaty to Queen Victoria appealing to her to intervene and stop the illegal opium trade that was destroying the health of the Chinese people. It is thought that Commissioner Lin’s correspondence was never seen by Queen Victoria.

Click here to read Lin Zuxu's letter to Queen Victoria

The First Opium War (1839–42) was spearheaded by the Nemesis, a British steam-powered gun-boat, that made its way to Canton where it helped to decimate the Chinese war junks defending the Pearl River Delta. The capitulation of China resulted in the Treaty of Nanking, under which China was forced to pay a large indemnity toBritain in payment for opium previously seized and destroyed by Commissioner Lin.

Hong Kong Island was also ceded to British Empire, the first of five treaty ports established along the Chinese coast. The Chinese market was opened up to the opium traders of Britain and other nations including the Americans who sourced their opium from Turkey.

The Qing court reacted to the ever increasing problem of opium addiction in its people and a Secound Opium War fought by Britain and France against China lasted from 1856 until 1860 and led to the Treaty of Tientsin and legalised the importation and growing of opium in China.

Although the trade in tea, opium and spices underpinned the economics of the British East India Company it also traded in many other exotic goods in the form of art and luxury goods from India and China including painting, porcelain, silver and gems, embroidered silks and printed cottons, lacquer-ware.

Iconography - side A – the 19th Century

Britain

UK crewel woolen embroidery on silk, 19

th Century and in the style of ‘William and Mary’ - the following extract from the UK accredited dealer:

‘Two English crewel panels, 19th century in the late 17th or early 18th century manner, each silk panel with wool work embroidered decoration and gold braided border, most likely originally part of tester bed drapery, in later gilt frames, with restorations. One panel centred by an emperor seated in a temple with stylised flowers and branches with butterflies above, alongside two, one possibly a Buddhist monk, the other an South American with stylised feathered head dress. Below the emperor colourful birds of paradise and mammals play, along with further figures in exotic clothing, leading to the goddess Diana with her bow and hunting dog in pursuit of a Ho Ho bird, above butterflies and an Oriental house. The second panel is centred by a personification of America in the form of a dancing native Indian surrounded by exotic birds and foliage, above appears a fanciful scene of floating islands, each with figures embroidered to them, one with Far Eastern character being shaded with a parasol, the second with an Indo-Chinese trader next to a Portuguese Conquistador. Beneath the central figure appears a lady in traditional Chinese clothing, flanked by plants and a butterfly, large exotic flowers lead to a Ho-Ho bird with talon feet aside a Chinese gentleman pulling a cart with two birds upon it.’

- Crewel embroidery patterns were sources of imagery for printed Indian Chintz cottons made for the English market. …reference V&A publication Indian Chintz…..

The British government tried to ban the importing of printed Indian Cotton chintz as its popularity threatened sales of locally manufactured cottons.

The Morgan Library, New York

India

India is represented by woman in a bountiful Indian garden that grew opium and tea for the export market.

‘The British

East India Company established a monopoly on opium cultivation in the Indian province of

Bengal, where they developed a method of growing opium poppies cheaply and abundantly. Other Western countries also joined in the trade, including the

United States, which dealt in Turkish as well as Indian opium.’ ‘The East India Company did not carry the opium itself but, because of the Chinese ban, farmed it out to “country traders”—i.e., private traders who were licensed by the company to take goods from India to China. The country traders sold the opium to smugglers along the Chinese coast. The gold and silver the traders received from those sales were then turned over to the East India Company. In China the company used the gold and silver it received to purchase goods that could be sold profitably in England.’ The Editors of the Encyclopaedia Britannica,

https://www.britannica.com/topic/opium-trade

Princess under arch. India, Gujarat or Lahore (Pakistan), early 17

th century. Velvet, brocaded and pile-warp substitution: silk and gilt-metal thread; 143x69cms. The David Collection, Copenhagen.

China

‘The amount of opium imported into China increased from about 200 chests annually in 1729 to roughly 1,000 chests in 1767 and then to about 10,000 per year between 1820 and 1830. The weight of each chest varied somewhat—depending on point of origin—but averaged approximately 140 pounds (63.5 kg). By 1838 the amount had grown to some 40,000 chests imported into China annually. The

balance of payments for the first time began to run against China and in favour of Britain.

Meanwhile, a network of opium distribution had formed throughout China, often with the connivance of corrupt officials. Levels of opium addiction grew so high that it began to affect the imperial troops and the official classes. The efforts of the Qing

dynasty to enforce the opium restrictions resulted in two armed conflicts between China and the West, known as the

Opium Wars, both of which China lost and which resulted in various measures that contributed to the decline of the Qing. The first war, between Britain and China (1839–42), did not legalize the trade, but it did halt Chinese efforts to stop it. In the second Opium War (1856–60)—fought between a British-French alliance and China—the Chinese government was forced to legalize the trade, though it did levy a small import tax on opium. By that time opium imports to China had reached 50,000 to 60,000 chests a year, and they continued to increase for the next three decades.’ ,

https://www.britannica.com/topic/opium-trade

Costume of Lin ZeXu a mandarin of the first rank

scholar-official of the

Qing dynasty

who was appointed by the

Daoguang Emperor to effect a ban on the import of opium to China. In 1839 he appealed directly to Queen Victoria to stop the opium trade.

Lin Zexu's "Letter of Advice to Queen Victoria" was written before the outbreak of the Opium Wars. It was a remarkably frank document, especially given the usual highly stylized language of Chinese diplomacy. There remains some question whether Queen Victoria ever read the letter. Ssuyu Teng and John Fairbank, China's Response to the West (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1954)

As first rank official of the Qing Dynasty Lin ZeXu was entitled to wear a mandarin square with the image of the red-capped crane.

The Spacing Vases

There are two identical vases that make up the five-vase garniture that carry images of the cultivation, trade and usage of the two drugs of the Silver Triangle – tea and opium – they are used as spacers and placed in between the major three vases. These spacer vases carry imagery that defines Britain’s response to its economy’s ‘trade imbalance’ with China. Images consist of botanical illustrations of the Papaver Somniferum (opium poppy) and Camellia Seninsis (tea plant); the western imagination of the East (Orientalism) romantically depicting opium smoking and tea drinking and the super fast ships that delivered the goods.

The Opium Vase

‘A Mandarin sits on a mat, smoking a long opium pipe. Coloured aquatint by Sigismond Himely, 1820

This was also the time when foreign traders were making great profits from smuggling opium into China in specially constructed “fast crab” (快蟹) rowing boats, which could outrun all government vessels. History of the Port of Hong Kong and Marine Department, Editor-in chief: Lau Chi-pang

The Tea Vase

Although the tea tree is native to India (Camellia Sinensis Assam) it was tea plants from China (Camellia Sinensis) established the tea growing industry in Assam, India. The introduction of Chinese tea plants, different from Indian tea, to India is commonly credited to

Robert Fortune, who spent about two and a half years, from 1848 to 1851, in China working of behalf of the

Royal Horticultural Society of London. Fortune employed many different means to steal tea plants and seedlings, which were regarded as property of the Chinese empire. He also used

Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward's portable

Wardian cases to sustain the plants. Using these small greenhouses, Fortune introduced 20,000 tea plants and seedlings to the

Darjeelingregion of India, on steep slopes in the foothills of the

Himalayas, with the

acid soil liked by

Camellia plants. He also brought a group of trained Chinese tea workers who would facilitate the production of tea leaves. With the exception of a few plants which survived in established Indian gardens, most of the Chinese tea plants Fortune introduced to India perished. The technology and knowledge that was brought over from China was instrumental in the later flourishing of the Indian tea industry using Chinese varieties, especially

Darjeeling tea, which continues to use Chinese strains.

Camellia Sinensis – image from Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection.

Tea Ceremony (Groeninge Museum, Bruges

Image of the Cutty Sark tea clipper by Frederick Tudgay, 1872.

Iconography Side B – Cultural highlights of the legacy of trade

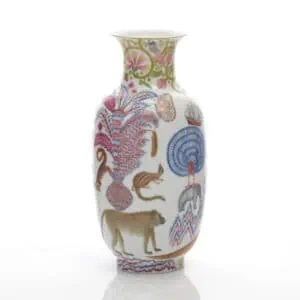

Chinese Vase

Qing Dynasty, Famille Rose painting on glazed porcelain, collection unknown.

Porcelain Vase

Top section – Chinese export ware for the English market, hand-painted under-glaze cobalt on porcelain plate probably 19

th Century, collection unknown.

Mid section - Study of poppies, composition Robin Best

Bottom section – River Landscape with willow and buildings, 1760, blue cobalt painting on porcelain, Hallwyl Museum, Sweden.

Indian Vase

Painted and dyed cotton chintz, Coromandel Coast, first quarter 18

th Century, Victoria and Albert Museum

Cotton Vase

Top Section – Bats and Poppies printed textile, M P Verneuil c. 1897, collection unknown

Mid section – Dark Satanic Mills, Cyril Mann, 1925, collection unknown

Bottom section – Hunting Scene, chintz for Portuguese market, collection unknown

English Vase – ‘Turner’s Willow’, transfer ware, Mason ironstone, early 19

th century, collection unknown.

UK crewel woolen embroidery on silk, 19th Century and in the style of ‘William and Mary’ - the following extract from the UK accredited dealer:

‘Two English crewel panels, 19th century in the late 17th or early 18th century manner, each silk panel with wool work embroidered decoration and gold braided border, most likely originally part of tester bed drapery, in later gilt frames, with restorations. One panel centred by an emperor seated in a temple with stylised flowers and branches with butterflies above, alongside two, one possibly a Buddhist monk, the other an South American with stylised feathered head dress. Below the emperor colourful birds of paradise and mammals play, along with further figures in exotic clothing, leading to the goddess Diana with her bow and hunting dog in pursuit of a Ho Ho bird, above butterflies and an Oriental house. The second panel is centred by a personification of America in the form of a dancing native Indian surrounded by exotic birds and foliage, above appears a fanciful scene of floating islands, each with figures embroidered to them, one with Far Eastern character being shaded with a parasol, the second with an Indo-Chinese trader next to a Portuguese Conquistador. Beneath the central figure appears a lady in traditional Chinese clothing, flanked by plants and a butterfly, large exotic flowers lead to a Ho-Ho bird with talon feet aside a Chinese gentleman pulling a cart with two birds upon it.’

- Crewel embroidery patterns were sources of imagery for printed Indian Chintz cottons made for the English market. …reference V&A publication Indian Chintz…..

The British government tried to ban the importing of printed Indian Cotton chintz as its popularity threatened sales of locally manufactured cottons.

UK crewel woolen embroidery on silk, 19th Century and in the style of ‘William and Mary’ - the following extract from the UK accredited dealer:

‘Two English crewel panels, 19th century in the late 17th or early 18th century manner, each silk panel with wool work embroidered decoration and gold braided border, most likely originally part of tester bed drapery, in later gilt frames, with restorations. One panel centred by an emperor seated in a temple with stylised flowers and branches with butterflies above, alongside two, one possibly a Buddhist monk, the other an South American with stylised feathered head dress. Below the emperor colourful birds of paradise and mammals play, along with further figures in exotic clothing, leading to the goddess Diana with her bow and hunting dog in pursuit of a Ho Ho bird, above butterflies and an Oriental house. The second panel is centred by a personification of America in the form of a dancing native Indian surrounded by exotic birds and foliage, above appears a fanciful scene of floating islands, each with figures embroidered to them, one with Far Eastern character being shaded with a parasol, the second with an Indo-Chinese trader next to a Portuguese Conquistador. Beneath the central figure appears a lady in traditional Chinese clothing, flanked by plants and a butterfly, large exotic flowers lead to a Ho-Ho bird with talon feet aside a Chinese gentleman pulling a cart with two birds upon it.’

- Crewel embroidery patterns were sources of imagery for printed Indian Chintz cottons made for the English market. …reference V&A publication Indian Chintz…..

The British government tried to ban the importing of printed Indian Cotton chintz as its popularity threatened sales of locally manufactured cottons.

The Morgan Library, New York

India

India is represented by woman in a bountiful Indian garden that grew opium and tea for the export market.

‘The British East India Company established a monopoly on opium cultivation in the Indian province of Bengal, where they developed a method of growing opium poppies cheaply and abundantly. Other Western countries also joined in the trade, including the United States, which dealt in Turkish as well as Indian opium.’ ‘The East India Company did not carry the opium itself but, because of the Chinese ban, farmed it out to “country traders”—i.e., private traders who were licensed by the company to take goods from India to China. The country traders sold the opium to smugglers along the Chinese coast. The gold and silver the traders received from those sales were then turned over to the East India Company. In China the company used the gold and silver it received to purchase goods that could be sold profitably in England.’ The Editors of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/opium-trade

The Morgan Library, New York

India

India is represented by woman in a bountiful Indian garden that grew opium and tea for the export market.

‘The British East India Company established a monopoly on opium cultivation in the Indian province of Bengal, where they developed a method of growing opium poppies cheaply and abundantly. Other Western countries also joined in the trade, including the United States, which dealt in Turkish as well as Indian opium.’ ‘The East India Company did not carry the opium itself but, because of the Chinese ban, farmed it out to “country traders”—i.e., private traders who were licensed by the company to take goods from India to China. The country traders sold the opium to smugglers along the Chinese coast. The gold and silver the traders received from those sales were then turned over to the East India Company. In China the company used the gold and silver it received to purchase goods that could be sold profitably in England.’ The Editors of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/opium-trade

Princess under arch. India, Gujarat or Lahore (Pakistan), early 17th century. Velvet, brocaded and pile-warp substitution: silk and gilt-metal thread; 143x69cms. The David Collection, Copenhagen.

China

‘The amount of opium imported into China increased from about 200 chests annually in 1729 to roughly 1,000 chests in 1767 and then to about 10,000 per year between 1820 and 1830. The weight of each chest varied somewhat—depending on point of origin—but averaged approximately 140 pounds (63.5 kg). By 1838 the amount had grown to some 40,000 chests imported into China annually. The balance of payments for the first time began to run against China and in favour of Britain.

Meanwhile, a network of opium distribution had formed throughout China, often with the connivance of corrupt officials. Levels of opium addiction grew so high that it began to affect the imperial troops and the official classes. The efforts of the Qing dynasty to enforce the opium restrictions resulted in two armed conflicts between China and the West, known as the Opium Wars, both of which China lost and which resulted in various measures that contributed to the decline of the Qing. The first war, between Britain and China (1839–42), did not legalize the trade, but it did halt Chinese efforts to stop it. In the second Opium War (1856–60)—fought between a British-French alliance and China—the Chinese government was forced to legalize the trade, though it did levy a small import tax on opium. By that time opium imports to China had reached 50,000 to 60,000 chests a year, and they continued to increase for the next three decades.’ , https://www.britannica.com/topic/opium-trade

Princess under arch. India, Gujarat or Lahore (Pakistan), early 17th century. Velvet, brocaded and pile-warp substitution: silk and gilt-metal thread; 143x69cms. The David Collection, Copenhagen.

China

‘The amount of opium imported into China increased from about 200 chests annually in 1729 to roughly 1,000 chests in 1767 and then to about 10,000 per year between 1820 and 1830. The weight of each chest varied somewhat—depending on point of origin—but averaged approximately 140 pounds (63.5 kg). By 1838 the amount had grown to some 40,000 chests imported into China annually. The balance of payments for the first time began to run against China and in favour of Britain.

Meanwhile, a network of opium distribution had formed throughout China, often with the connivance of corrupt officials. Levels of opium addiction grew so high that it began to affect the imperial troops and the official classes. The efforts of the Qing dynasty to enforce the opium restrictions resulted in two armed conflicts between China and the West, known as the Opium Wars, both of which China lost and which resulted in various measures that contributed to the decline of the Qing. The first war, between Britain and China (1839–42), did not legalize the trade, but it did halt Chinese efforts to stop it. In the second Opium War (1856–60)—fought between a British-French alliance and China—the Chinese government was forced to legalize the trade, though it did levy a small import tax on opium. By that time opium imports to China had reached 50,000 to 60,000 chests a year, and they continued to increase for the next three decades.’ , https://www.britannica.com/topic/opium-trade

Costume of Lin ZeXu a mandarin of the first rank scholar-official of the Qing dynasty

who was appointed by the Daoguang Emperor to effect a ban on the import of opium to China. In 1839 he appealed directly to Queen Victoria to stop the opium trade.

Lin Zexu's "Letter of Advice to Queen Victoria" was written before the outbreak of the Opium Wars. It was a remarkably frank document, especially given the usual highly stylized language of Chinese diplomacy. There remains some question whether Queen Victoria ever read the letter. Ssuyu Teng and John Fairbank, China's Response to the West (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1954)

As first rank official of the Qing Dynasty Lin ZeXu was entitled to wear a mandarin square with the image of the red-capped crane.

The Spacing Vases

There are two identical vases that make up the five-vase garniture that carry images of the cultivation, trade and usage of the two drugs of the Silver Triangle – tea and opium – they are used as spacers and placed in between the major three vases. These spacer vases carry imagery that defines Britain’s response to its economy’s ‘trade imbalance’ with China. Images consist of botanical illustrations of the Papaver Somniferum (opium poppy) and Camellia Seninsis (tea plant); the western imagination of the East (Orientalism) romantically depicting opium smoking and tea drinking and the super fast ships that delivered the goods.

The Opium Vase

Costume of Lin ZeXu a mandarin of the first rank scholar-official of the Qing dynasty

who was appointed by the Daoguang Emperor to effect a ban on the import of opium to China. In 1839 he appealed directly to Queen Victoria to stop the opium trade.

Lin Zexu's "Letter of Advice to Queen Victoria" was written before the outbreak of the Opium Wars. It was a remarkably frank document, especially given the usual highly stylized language of Chinese diplomacy. There remains some question whether Queen Victoria ever read the letter. Ssuyu Teng and John Fairbank, China's Response to the West (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1954)

As first rank official of the Qing Dynasty Lin ZeXu was entitled to wear a mandarin square with the image of the red-capped crane.

The Spacing Vases

There are two identical vases that make up the five-vase garniture that carry images of the cultivation, trade and usage of the two drugs of the Silver Triangle – tea and opium – they are used as spacers and placed in between the major three vases. These spacer vases carry imagery that defines Britain’s response to its economy’s ‘trade imbalance’ with China. Images consist of botanical illustrations of the Papaver Somniferum (opium poppy) and Camellia Seninsis (tea plant); the western imagination of the East (Orientalism) romantically depicting opium smoking and tea drinking and the super fast ships that delivered the goods.

The Opium Vase

‘A Mandarin sits on a mat, smoking a long opium pipe. Coloured aquatint by Sigismond Himely, 1820

‘A Mandarin sits on a mat, smoking a long opium pipe. Coloured aquatint by Sigismond Himely, 1820

This was also the time when foreign traders were making great profits from smuggling opium into China in specially constructed “fast crab” (快蟹) rowing boats, which could outrun all government vessels. History of the Port of Hong Kong and Marine Department, Editor-in chief: Lau Chi-pang

The Tea Vase

Although the tea tree is native to India (Camellia Sinensis Assam) it was tea plants from China (Camellia Sinensis) established the tea growing industry in Assam, India. The introduction of Chinese tea plants, different from Indian tea, to India is commonly credited to Robert Fortune, who spent about two and a half years, from 1848 to 1851, in China working of behalf of the Royal Horticultural Society of London. Fortune employed many different means to steal tea plants and seedlings, which were regarded as property of the Chinese empire. He also used Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward's portable Wardian cases to sustain the plants. Using these small greenhouses, Fortune introduced 20,000 tea plants and seedlings to the Darjeelingregion of India, on steep slopes in the foothills of the Himalayas, with the acid soil liked by Camellia plants. He also brought a group of trained Chinese tea workers who would facilitate the production of tea leaves. With the exception of a few plants which survived in established Indian gardens, most of the Chinese tea plants Fortune introduced to India perished. The technology and knowledge that was brought over from China was instrumental in the later flourishing of the Indian tea industry using Chinese varieties, especially Darjeeling tea, which continues to use Chinese strains.

This was also the time when foreign traders were making great profits from smuggling opium into China in specially constructed “fast crab” (快蟹) rowing boats, which could outrun all government vessels. History of the Port of Hong Kong and Marine Department, Editor-in chief: Lau Chi-pang

The Tea Vase

Although the tea tree is native to India (Camellia Sinensis Assam) it was tea plants from China (Camellia Sinensis) established the tea growing industry in Assam, India. The introduction of Chinese tea plants, different from Indian tea, to India is commonly credited to Robert Fortune, who spent about two and a half years, from 1848 to 1851, in China working of behalf of the Royal Horticultural Society of London. Fortune employed many different means to steal tea plants and seedlings, which were regarded as property of the Chinese empire. He also used Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward's portable Wardian cases to sustain the plants. Using these small greenhouses, Fortune introduced 20,000 tea plants and seedlings to the Darjeelingregion of India, on steep slopes in the foothills of the Himalayas, with the acid soil liked by Camellia plants. He also brought a group of trained Chinese tea workers who would facilitate the production of tea leaves. With the exception of a few plants which survived in established Indian gardens, most of the Chinese tea plants Fortune introduced to India perished. The technology and knowledge that was brought over from China was instrumental in the later flourishing of the Indian tea industry using Chinese varieties, especially Darjeeling tea, which continues to use Chinese strains.

Camellia Sinensis – image from Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection.

Camellia Sinensis – image from Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection.

Tea Ceremony (Groeninge Museum, Bruges

Tea Ceremony (Groeninge Museum, Bruges

Image of the Cutty Sark tea clipper by Frederick Tudgay, 1872.

Iconography Side B – Cultural highlights of the legacy of trade

Chinese Vase

Qing Dynasty, Famille Rose painting on glazed porcelain, collection unknown.

Porcelain Vase

Top section – Chinese export ware for the English market, hand-painted under-glaze cobalt on porcelain plate probably 19th Century, collection unknown.

Mid section - Study of poppies, composition Robin Best

Bottom section – River Landscape with willow and buildings, 1760, blue cobalt painting on porcelain, Hallwyl Museum, Sweden.

Indian Vase

Painted and dyed cotton chintz, Coromandel Coast, first quarter 18th Century, Victoria and Albert Museum

Cotton Vase

Top Section – Bats and Poppies printed textile, M P Verneuil c. 1897, collection unknown

Mid section – Dark Satanic Mills, Cyril Mann, 1925, collection unknown

Bottom section – Hunting Scene, chintz for Portuguese market, collection unknown

English Vase – ‘Turner’s Willow’, transfer ware, Mason ironstone, early 19th century, collection unknown.

Image of the Cutty Sark tea clipper by Frederick Tudgay, 1872.

Iconography Side B – Cultural highlights of the legacy of trade

Chinese Vase

Qing Dynasty, Famille Rose painting on glazed porcelain, collection unknown.

Porcelain Vase

Top section – Chinese export ware for the English market, hand-painted under-glaze cobalt on porcelain plate probably 19th Century, collection unknown.

Mid section - Study of poppies, composition Robin Best

Bottom section – River Landscape with willow and buildings, 1760, blue cobalt painting on porcelain, Hallwyl Museum, Sweden.

Indian Vase

Painted and dyed cotton chintz, Coromandel Coast, first quarter 18th Century, Victoria and Albert Museum

Cotton Vase

Top Section – Bats and Poppies printed textile, M P Verneuil c. 1897, collection unknown

Mid section – Dark Satanic Mills, Cyril Mann, 1925, collection unknown

Bottom section – Hunting Scene, chintz for Portuguese market, collection unknown

English Vase – ‘Turner’s Willow’, transfer ware, Mason ironstone, early 19th century, collection unknown.